Equity Study reaches 4000 participants

Post filed in: Equity

Government is at its best when it works for everyone. GSA’s Equity Study on Remote Identity Proofing, launched last fall, was designed to understand how to ensure that an increasingly important aspect of modern technology – verifying your identity online – works for everyone. Remote identity proofing is the process of verifying who an individual says they are, and it’s a step that many agencies now require in order for individuals to access government services and benefits online.

By the end of April, the Equity Study team achieved the study’s goal of recruiting 4,000 participants from demographically diverse communities. By achieving this major milestone, academic experts can now start to analyze the data.

As a next step, the Equity Study team is engaging those academic experts to implement rigorous research methods and publish a scientific peer-reviewed report. The peer-review process will ensure accuracy and foster important dialogue around how to measure equity in technology.

Building and executing a study of this size showcases how a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach can help government work better, and is part of GSA and the Biden-Harris Administration’s broader efforts to find ways to deliver government services equitably to the public. The full peer-reviewed results, set to be released in 2025, will provide important insights to both GSA and agencies government-wide in how they build better service delivery for the public. GSA products and programs, such as Login.gov, are also looking at how they might thoughtfully incorporate these findings into their processes and approaches.

Getting to 4,000

The goal of 4,000 full study completions was set to allow for equal representation for federally recognized racial and ethnic groups, more specifically Asian-American/Pacific Islander, American Indian, Black/African-American, Hispanic/Latino, and white participants. This gives GSA the statistical confidence to distinguish between random errors and real findings in identity proofing results.

For nine months, participants were recruited via outreach with key groups, such as colleges, universities, and nonprofits, as well as word-of-mouth and social media.

GSA plans to share lessons learned as part of this successful recruiting effort to help inform how future government research projects can achieve representative participation from diverse communities.

Analyzing the data

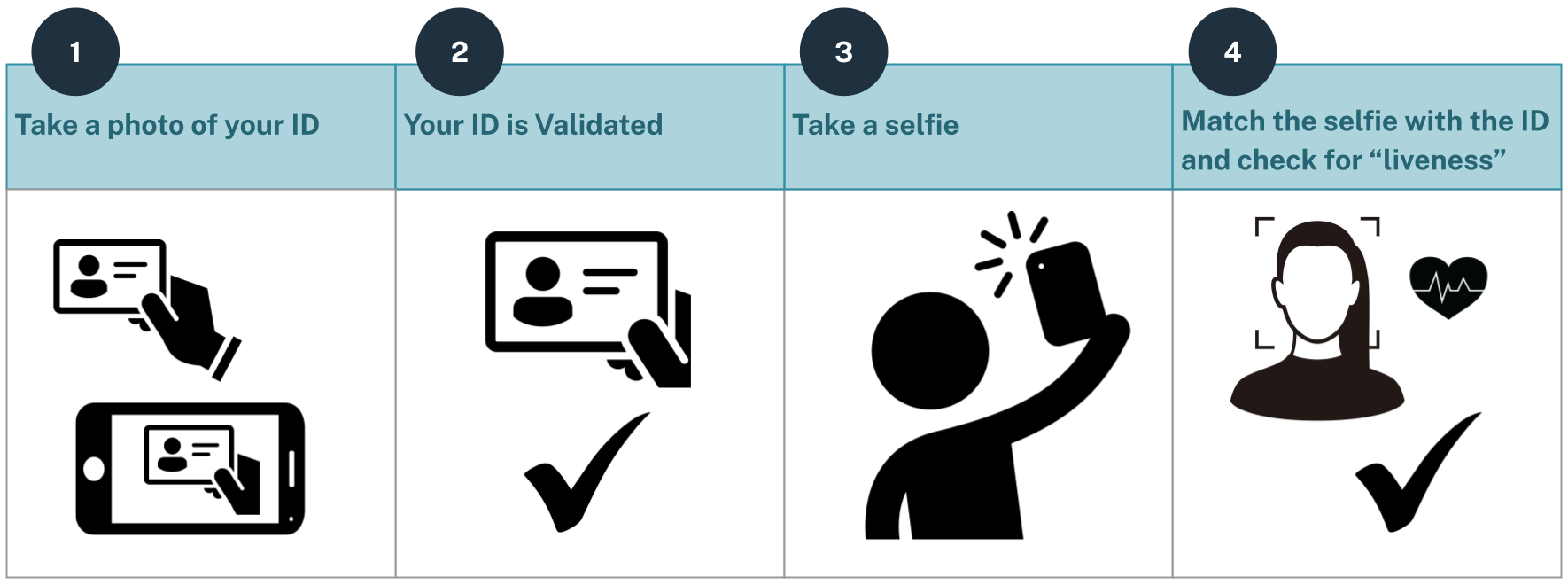

The study examined whether the various algorithms and methods used in remote identity proofing introduce bias into the process of verifying someone’s identity. While safeguarding the use of their data, the study asked volunteers to complete the following steps on their own (i.e., not in a lab):

- Capture pictures of the front and back of their IDs.

- Take a selfie.

- Provide personal information for validation.

For the image capture and comparison process from Steps 1 and 2, the study asked participants to test five different versions of this process to help us understand common problems and challenges with various systems. The tests evaluate the “false rejection rate” for these systems to answer the question: how often do these systems make mistakes and reject real people with valid IDs?

Next, the average false rejection rate will be compared with the results for a specific demographic (e.g. race, gender). Ideally, all demographics are rejected at a similar rate. However, when a specific demographic exhibits rejection rates that are significantly higher or lower than the average (within a margin of confidence) that suggests there might be bias in the process.

Further analysis

As the research team analyzes the data, they will examine the results from multiple perspectives, including:

- How does the user experience affect the chances of taking high-quality pictures that lead to accurate proofing results?

- Which step of the process had the highest rate of false rejections? Why? Were there any demographic trends at any steps?

- How does a person’s phone model affect the process? Do people using newer or more expensive phones have lower false rejection rates?

Additional analysis will explore each step of the process in detail to determine whether there are biases with algorithms or systems at each step of the user journey.

GSA looks forward to using the results of the study to help GSA and other federal agencies advance equity in new, modern technologies and deliver services more effectively for the public.

U.S. General Services Administration

U.S. General Services Administration