Lafayette Park and the blocks that surround it, known as Lafayette Square, feature prominently in American history. The area is also notable for the high concentration of historic buildings under GSA’s stewardship. The seven-acre park contains green space and public art. It is lined by nineteenth-century row-houses, and bordered by Pennsylvania Avenue to the south, Jackson Place to the west, and Madison Place to the east; H Street borders it to the north.

Originally known as “President’s Park,” the land served as a construction staging area for the White House in 1800. But before it became a park and an historic landmark, the land served at various points as a racetrack, a graveyard, a zoo, a slave market, an encampment for soldiers during the War of 1812, and the site of many political protests and celebrations. (Lafayette Park continues to serve as a gathering place for public events.) The land was fenced during Thomas Jefferson’s presidency (which ran from 1801 to 1809). The land was then made part of the executive mansion grounds.

The park itself is named for the Marquis de Lafayette, the French military leader whose involvement was crucial in securing victory in the American Revolutionary War. Many of the structures surrounding Lafayette Park are now owned and or maintained by GSA. This includes Blair House (President’s Guest House), Dolley Madison’s House, Trowbridge House, the Cosmos Club (which includes the Benjamin Ogle Tayloe House, and the Cornelia Knower Marcy House).

History

Although now an elegantly designed park, Lafayette Square had humble beginnings. During the 1700s, it was a plot of land used and reused as a family graveyard, a racetrack, a zoo, an apple orchard, and a slave market.

This changed when the land was purchased as part of the White House grounds. Crews building the original White House used it for construction staging, a purpose for which it was used again after the White House was torched by the British during the War of 1812.

In the years immediately following the Revolutionary War, the grounds were cleared, graded, and planted with trees. Architect Charles Bullfinch devised the plan of what was called “the President’s Park,” a nod to its adjacency to the White House.

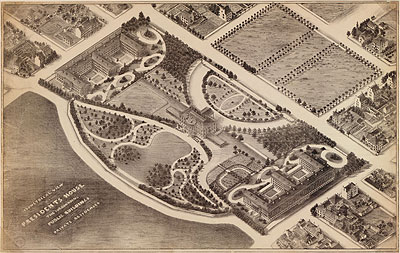

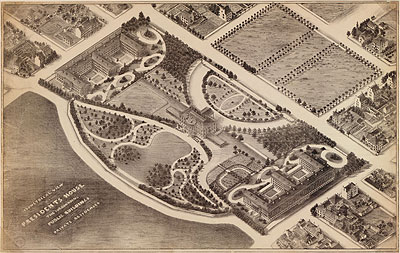

Isometrical view of the Presidents House, the surrounding public buildings, and private residences. This 1857 map anticipates the appearance of new, expanded government buildings, some never realized, and omits other landmarks such as the Andrew Jackson statue in Lafayette Park, which first appeared in the park in 1853. Credit: Library of Congress.

President Thomas Jefferson personally involved himself in the development of the President’s Park; he decided to erect 12-foot stone wall fencing on the south border and rail fencing on the other three. He also saw to the landscaping of the executive mansion grounds. In 1803, Jefferson ordered Pennsylvania Avenue to cut through President’s Park forming two sections.

Two of the earliest buildings constructed near the park were St. John’s Church, in 1815, and Commodore Stephen Decatur and his wife Susan’s home, in 1818. Benjamin H. Latrobe, American’s first professional architect and engineer, designed both buildings. The Decatur House, as it became known, was the first private residence in the White House neighborhood. Decatur did not long enjoy his new home; within fourteen months of moving in, he was killed in a duel on March 22, 1820. Afterwards, Susan Decatur moved out of the house and rented it to a succession of Secretaries of State, including Henry Clay, whose slave, Charlotte Dupuy, sued him for her freedom while living in the house. Decatur House remains one of very few remaining examples of slave quarters in an urban area, and the only one we know of that is evidence that African Americans were held in bondage in sight of the White House.

Over the next fifty years, the square became one of the city’s most fashionable and prominent neighborhoods. Its location near the White House attracted numerous residents of note, including members of the Cabinet, Congress, and the diplomatic corps. The area remained a highly desirable residential district into the twentieth century.

The attached houses lining the east and west sides of Lafayette Park are typical of the era—three stories with a basement and three bays wide, with off-center entrances. All are of masonry construction, with either sandstone or brick decorative trim and door surrounds.

Because of this proximity, houses soon began springing up around the square with notable occupants, including: the banker William Wilson Corcoran; two Secretaries of State, Martin van Buren and Henry Clay; First Lady Dolley Madison; Presidential Secretary, John Hay; and historian and author Henry Adams, the great-grandson of President John Adams and the grandson of President John Quincy Adams. Adams expressed the enormous significance of the square, writing that, “Beyond the Square, the country began.”

In 1851 President Millard Fillmore commissioned landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing to develop new plans for the city’s park spaces, including Lafayette Square. Downing was an advocate of the Gothic Revival and Picturesque styles. His design for the park features picturesque walkways of intersection ovals that pass by fountains and open spaces. These would become ideal settings for statues.

Andrew Jackson Equestrian statue, Lafayette Park. This is the earliest known photograph (c. 1855) of the Jackson equestrian statue. It is in the collection of Saint John’s Episcopal Church, which can be seen beyond the park on H Street.

Two years later, sculptor Clark Mills’ equestrian statue of General Andrew Jackson became the first statue in the park; it was also the first bronze statue cast in the country, and the first equestrian statue in the world to feature a horse rearing up on its two hind legs.

The dedication of the Mills’ statue occasioned the installation of cast-iron fencing and new plantings. The unnamed streets on the west and east were named Jackson Place and Madison Place.

In 1891 a statue honoring Lafayette’s service in the American Revolution was unveiled on the southeast, the first of four significant bronze sculptures on the corners of the park, each depicting a foreign Revolutionary War hero who served under General George Washington: Lafayette (France), the Comte de Rochambeau (France), Friedrich Wilhelm, Baron von Steuben (Germany), and Tadcusz Kosciuszko (Poland).

As the government expanded in the 20th century, Lafayette Square’s surrounding neighborhood became less residential. The area provided more and more workspace for government workers and professional associations. As early as 1901, architect Cass Gilbert proposed a group of office buildings adjacent to the park, and although never executed, the idea remained active into the 1950s.

As the world entered the Great Depression, Lafayette Square saw the passing of its last residential home owner; Mary Chase Morris, the final resident of the O’Toole House at 730 Jackson Place, died. The home became office space. World War II followed on the heels of the Depression, and improvements and changes to Lafayette Square remained in limbo. Many of the materials used in construction, and the labor needed to build, was diverted to the war effort, slowing the pace of change to Lafayette Square and the nation.

Following the end of the war, during the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration, Gilbert’s plans for offices around Lafayette Park were renewed and a proposal for monumental, strikingly modern office buildings flanking Lafayette Square received funding from Congress. This would mean the destruction of the houses that had defined the neighborhood.

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy views a scale model of the historic preservation and redevelopment plans for Lafayette Square, Washington, DC. Architect of the Lafayette Square redevelopment, John Carl Warnecke, points to an area of the model. Photographer: Robert Knudsen. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Shortly before the plan’s fruition, in a watershed event for the historic preservation movement, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy intervened and lobbied the U.S. General Services Administration to stop imminent demolition of the historic houses. At the request of the John F. Kennedy administration, architect John Carl Warnecke conceptualized a plan through which the extant Madison Place and Jackson Place houses were restored and supplemented by new federal buildings designed to complement the historic setting.

Lafayette Square was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970, and the surrounding buildings are now occupied by a variety of federal agencies.

U.S. General Services Administration

U.S. General Services Administration